Phenotypic heterogeneity of Duplication Syndrome 22q11.2: relevance of genomic DNA analysis

Authors

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.37980/im.journal.ggcl.en.20252695Keywords:

22q11.2 duplication syndrome, chromosomal microarray, interstitial duplication, TOP3B geneAbstract

Background: 22q11.2 duplication syndrome (22q11.2DupS) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, including intellectual disability, dysmorphic features, and congenital anomalies. The phenotypic heterogeneity of 22q11.2DupS complicates both clinical diagnosis and management. Traditional screening methods, such as fetal ultrasound, often fail to detect these abnormalities early, leading to delayed diagnoses however, advances in chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) offer a promising opportunity to improve detection, particularly in high-risk pregnancies. Case presentation: This report describes a female patient with dysmorphic features, neurodevelopmental delay, and behavioral alterations, with no related family history or consanguinity. Genetic findings: The patient was diagnosed with 22q11.2DupS through genomic DNA analysis using the Agilent® SurePrint G3 Human CGH+SNP array, which identified a heterozygous interstitial duplication at chromosomal coordinates 22q11.22 affecting the TOP3B gene, currently not associated with any known pathology but implicated in genomic stability and cellular aging. Discussion: 22q11.2DupS is a rare chromosomal disorder with a wide phenotypic spectrum, including intellectual disability, dysmorphic features, and congenital anomalies despite increasing recognition, comprehensive descriptions of its full clinical spectrum remain limited, and similar duplications have been classified with varying degrees of pathogenicity in public databases. Conclusion: 22q11.2DupS represents a complex clinical challenge due to its broad phenotypic spectrum, and early detection through advanced genetic testing such as CGH+SNP microarray analysis, along with genetic counseling and therapies including cognitive-behavioral and speech therapy, is essential for effective management as no specific therapies are available, treatment remains symptomatic.

INTRODUCTION

Chromosome 22q11.2 contains a region of low-copy number repeats (LCRs) that is particularly susceptible to unequal crossing over during meiosis, leading to the development of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) or 22q11.2 duplication syndrome (22q11.2DupS) [1].

Chromosome 22 exhibits a high susceptibility to non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) due to the abundance of LCRs, specifically designated as LCR-A through LCR-H within the 22q11.2 region. This recombination mechanism generates copy number variations (CNVs), such as duplications and deletions, characterized by recurrent breakpoints and diverse phenotypic presentations [2]. The 22q11.2 locus contains genes critical for brain development [3]. The 22q11.2 duplication syndrome (22q11.2DupS) is an autosomal dominant disorder resulting from an additional copy of a segment of chromosome 22. This duplication, along with deletions in the same region, arises due to unequal crossover events during meiosis I, which occur as a consequence of misalignment of low-copy repeat sequences (LCRs) within the 22q11 band [4].

The prevalence of 22q11.2 duplication syndrome (22q11.2DupS) in individuals with intellectual disability is estimated to be 1 in 700. Considering that approximately 6.5 million people in the United States have an intellectual disability, it is projected that there are around 9,285 cases of 22q11.2 duplication syndrome within this population [5].

The 22q11.2DupS is a rare chromosomal disorder characterized by a broad spectrum of phenotypic manifestations, including intellectual disability, dysmorphic features, and congenital anomalies. Despite increasing recognition of this condition, comprehensive descriptions of its full clinical spectrum remain limited [1].

In addition to structural anomalies, emerging evidence suggests that language development may be significantly affected in individuals with 22q11.2DupS. A study by Jente et al. (2023) found that children with 22q11.2 duplications exhibited notable language impairments when compared to the general population. Although both 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) and 22q11.2DupS are associated with language deficits, differences in the nature of these impairments have been observed. While 22q11.2DS is primarily characterized by word-level difficulties, individuals with 22q11.2DupS demonstrate more pronounced sentence-level impairments [6]. These findings underscore the need for further research to elucidate the neurodevelopmental impact of this condition.

Prenatal diagnosis of 22q11.2DupS presents significant challenges due to its phenotypic variability and incomplete penetrance [7]. Current screening methods rely heavily on fetal ultrasound to identify abnormalities that may prompt further genetic testing. However, factors such as fetal developmental variability, limitations in ultrasound technology, and operator experience can lead to missed diagnoses, particularly in the early stages of pregnancy [8]. Given the expanding role of chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) in prenatal diagnostics, there is potential for improved detection rates, particularly in pregnancies identified as high risk due to advanced maternal age or abnormal first-trimester screening results [9].

Early detection and timely supportive care, including genetic counseling and therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and speech therapy, are essential for effective management of this condition. Ongoing research is necessary to deepen understanding and improve the management of 22q11.2 duplication syndrome (22q11.2DupS) [4].

Identifying 22q11.2DupS through genetic testing not only confirms the diagnosis but also enables early intervention strategies, including specialized therapies for neurodevelopmental impairments, structured follow-up for congenital anomalies, and multidisciplinary care approaches aimed at improving long-term outcomes [4].

CASE REPORT

The case of an 11-year-5-month-old female is presented, born to non-consanguineous parents (both 32 years old at the time of conception), with a previous cesarean section. She was born at term with a weight of 2,500 g and a length of 50 cm. Prenatal ultrasound showed no abnormalities, and there were no signs of perinatal complications.

On physical examination, she presented dysmorphic features, including a broad forehead, widely spaced eyes, a bulbous nose, retrognathia, irregular dentition, a high-arched palate, and small, low-set ears. Additional findings included a webbed neck, global developmental delay, and mutism. She avoided eye contact and did not engage with the examiner.

Her medical history includes mild bilateral conductive hearing loss. Her surgical history includes adenoidectomy, turbinoplasty, tonsillectomy, and tympanostomy with ventilation tube placement on two occasions. She has been diagnosed with a mild to moderate cognitive deficit (IQ 40) and a primary language development disorder characterized by functional impairment of receptive and expressive language, based on a neuropsychological test report. She is currently enrolled in the third grade and has not undergone psychiatric assessment. A chromosomal karyotype analysis revealed a 46,XX result.

Considering the above, and emphasizing the importance of ruling out the presence of a genetic syndrome related to the patient’s phenotypic and neurodevelopmental-behavioral alterations in the absence of a related family history, as well as the need for a precise diagnosis to guide management, provide appropriate follow-up, determine prognosis, and offer genetic counseling—including assessment of heritability risk—chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), also known as comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), was requested. These molecular cytogenetic techniques allow for the detection of copy number variations (CNVs), such as deletions or duplications, which could explain her clinical presentation.

Results

Genomic DNA was extracted from a peripheral blood sample of the patient, followed by appropriate quality control procedures. Subsequently, labeling of both the patient’s DNA and the reference DNA (female control) was performed, followed by hybridization using the Agilent® SurePrint G3 Human CGH+SNP array 4x180K (array number: 252983083582_1_2-430046), according to established protocols of an accredited genomic laboratory. Data were scanned using SureScan®, with subsequent acquisition, quality assessment, and interpretation performed using Agilent CytoGenomics v5® software.

A heterozygous interstitial duplication of uncertain clinical significance was detected at chromosomal region 22q11.22, with genomic coordinates chr22:21959009_22202339. Similar-sized duplications have been reported in the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV) and the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD). Comparable duplications have also been classified as likely pathogenic and reported in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), mild intellectual disability, obsessive-compulsive behavior, and schizophrenia. This duplication partially overlaps a locus identified by the Clinical Genome Resource as having evidence of triplosensitivity (https://clinicalgenome.org/).

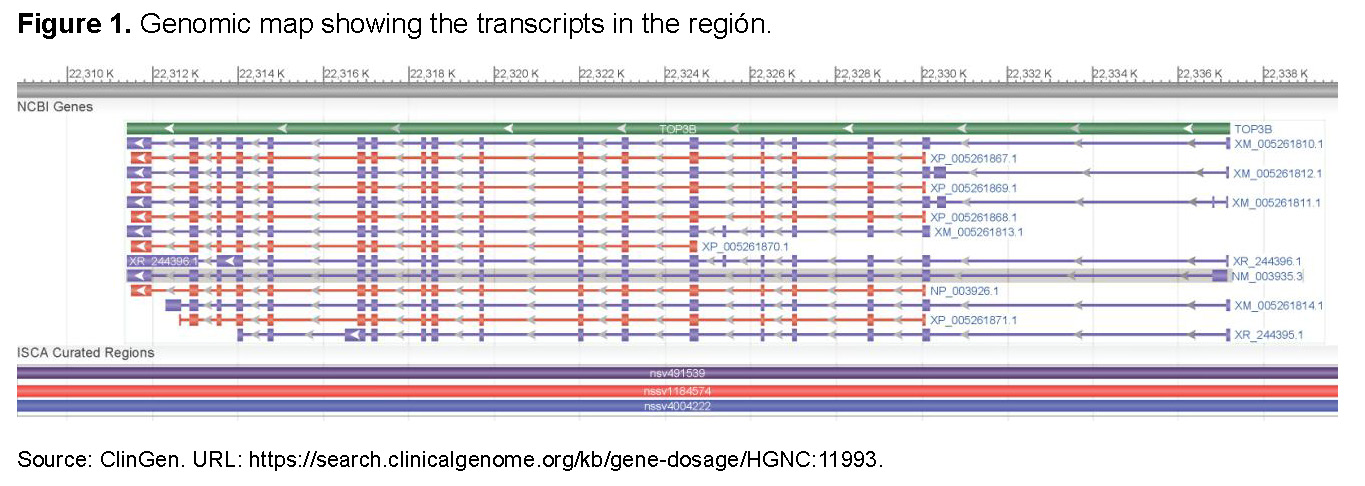

Data reanalysis was performed using applied bioinformatics approaches and by querying this coordinate in GeneScout Location (NCBI, GRCh38 [hg38]): chr22:21,957,025–21,982,787. This region corresponds to chromosome 22q11.2 microduplication syndrome, an autosomal dominant condition reported in multiple case studies (MIM Phenotype 608363). The TOP3B DNA topoisomerase III beta gene is located within this interval (Gene MIM Number: 603582; Dosage ID: ISCA-14015; ClinGen Curation ID: CCID:008026, See Figure 1).

A search in the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) database for the TOP3B gene (NCBIGene: 8940), located at 22q11.22, indicates that TOP3B encodes a DNA topoisomerase involved in regulating DNA topology during transcription. This enzyme facilitates transient cleavage and re-ligation of a single DNA strand, allowing strand passage and relaxation of supercoils. TOP3B interacts with the DNA helicase SGS1 and plays a crucial role in DNA recombination, genomic stability, and cellular aging. Reduced expression of this gene has also been associated with increased survival in breast cancer patients. A TOP3B pseudogene is also present on chromosome 22.

A summary of the reviewed literature includes descriptions of patients with microduplications spanning 22q11.21–q11.23, with de novo, maternal, and unknown inheritance patterns, including the LCR22D–LCR22E region containing TOP3B. These patients exhibited heterogeneous phenotypes, including developmental delay, attention deficits, mild intellectual disability, dysmorphic features, and hypotonia. The reported duplications encompassed several genes in addition to TOP3B, and a wide phenotypic spectrum was observed.

Discussion

Duplications encompassing the LCR-A to LCR-D interval have been associated with a spectrum of clinical manifestations, ranging from mild neurodevelopmental impairments to severe congenital anomalies, including bladder exstrophy and cardiac malformations. The phenotypic heterogeneity of 22q11.2DupS complicates clinical diagnosis and management [2].

Previous studies, such as that by Mary L. et al. (2021), have contributed insights into the prevalence of clinical features associated with 22q11.2DupS. Their analysis of 42 patients, supplemented by 20 additional cases from the literature, reported congenital heart defects (26.1%), cleft or submucous cleft palate (11.7%), growth failure (27.4%), microcephaly (16.3%), macrocephaly (4.9%), hearing loss (16.2%), vision anomalies (28.1%), intellectual disability (24.3%), learning disabilities (22.4%), developmental delay (58.1%), seizures (11.3%), autism spectrum disorder (13.4%), and attention deficit disorder (ADD)/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (18.5%) [2]. Patients with 22q11.2DupS have also been reported to present a variety of congenital heart disease phenotypes, including anomalous pulmonary venous connections, d-transposition of the great arteries, Ebstein’s anomaly, and vascular rings [9].

In the study by Barkit L.E. (2021), birth history was available for 37 subjects. Most patients (86%) were born at term (n = 32), and prenatal ultrasound anomalies were reported in four pregnancies. Birth weights and lengths were recorded for 33 and 27 subjects, respectively, with 67% having birth weights below the 50th percentile (n = 22). CGH or SNP microarray was the most frequently used diagnostic method (78.6%, n = 33), followed by FISH (9.5%, n = 4), qPCR (9.5%, n = 4), and prenatal diagnosis using the MaterniT® Genome assay (2.4%, n = 1). The mean age at diagnosis was 3.5 years (SD 4.2 years), highlighting delayed recognition in many cases [1].

The condition encompasses a wide range of congenital anomalies and neurodevelopmental challenges. The high prevalence of congenital heart defects, growth failure, and vision anomalies highlights the importance of early and comprehensive medical evaluation. Given the significant burden of neurodevelopmental disorders, including intellectual disability, developmental delay, autism spectrum disorder, and ADHD/ADD, routine neurocognitive assessment should be incorporated into clinical follow-up [1].

Prenatal screening and diagnosis of 22q11.2DupS remain challenging [8]. Li et al. (2023) reported two prenatal cases detected by noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) and confirmed by SNP array analysis of amniotic fluid. CNV-seq of maternal blood was used to characterize breakpoints and affected genes. Their findings emphasize phenotypic variability, the importance of prenatal diagnosis, and implications for genetic counseling [10]. Variability in ultrasound findings and limitations of screening programs result in many cases remaining undiagnosed until postnatal genetic testing [8]. The integration of chromosomal microarrays into prenatal care has improved detection of fetal chromosomal abnormalities, particularly in high-risk pregnancies [2].

Diagnosis based solely on clinical features is difficult, as most cases are not detectable by routine karyotyping. Chromosomal microarray analysis has significantly improved identification of chromosome 22 CNVs, enhancing diagnostic accuracy [11].

Currently, no specific therapies are available for 22q11.2DupS; therefore, management remains symptomatic and supportive [11].

In summary, 22q11.2DupS represents a complex genetic condition with a wide clinical spectrum. Continued research is required to improve early detection strategies and develop targeted interventions to address the medical and developmental challenges faced by affected individuals.

CONCLUSION

This case report highlights the complexity and phenotypic variability of 22q11.2 duplication syndrome (22q11.2DupS), emphasizing the challenges associated with diagnosis and individualized management. The findings underscore the importance of genomic testing, particularly chromosomal microarray analysis, in detecting copy number variations that may go unnoticed with other diagnostic approaches. Given the syndrome’s association with neurodevelopmental disorders and congenital anomalies, early detection and timely intervention—including genetic counseling and therapies such as cognitive-behavioral and speech therapy—are essential to improve prognosis and ensure appropriate follow-up.

In conclusion, this case reinforces the importance of integrating genomic medicine and systematic genomic data reanalysis in the evaluation of patients with neurodevelopmental disorders and congenital anomalies. Improving diagnostic accuracy and enabling early intervention can lead to more personalized and effective management strategies.

References

[1] Barkit LE, et al. 22q11.2 duplications: Expanding the clinical presentation. Am J Med Genet A. 2022;188(3):779–87.

[2] Mary, L., et al. Prenatal phenotype of 22q11 micro-duplications: A systematic review and report on 12 new cases. Eur J Med Genet. 2022;65:104422.

[3] Schleifer CH. Effects of gene dosage and development on subcortical nuclei volumes in individuals with 22q11.2 copy number variations. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2024;49(5):1024–32. doi:10.1038/s41386-023-01841-2.

[4] Balakrishnan RK, et al. A case of 22q11.2 microduplication syndrome with review of literature. Educ Adm Theory Pract. 2024;30(5):2256–2358.

[5] Mikulas C, et al. 22q11.2 duplication syndrome: A rare chromosomal disorder with variable phenotypical and clinical presentations. Scholar Pilot Valid Stud. 2023;4(1):14–7. doi:10.32778/SPVS.71366.2023.37.

[6] Verbesselt J, et al. Language profiles of school-aged children with 22q11.2 copy number variants. Genes. 2023;14(4):679.

[7] Jiang Y, et al. Prenatal diagnosis and genetic study of 22q11.2 microduplication in Chinese fetuses: A series of 31 cases and literature review. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2024;12(1):e2498.

[8] Wang X, et al. Preliminary study of noninvasive prenatal screening for 22q11.2 deletion/duplication syndrome using multiplex dPCR assay. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023;18(1):278.

[9] Butensky A. Cardiac evaluation of patients with 22q11.2 duplication syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2021;185(3):753–8. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.62011.

[10] Li H, Gong Y, Chen J, Xie L, Li B, Xiang Y, Xie M. Diagnosis of prenatal 22q11.2 duplication syndrome: a two-case study. J Genet. 2023;102(4).

[11] Jun KR. Deletion or Duplication Syndromes of Chromosome 22. J Interdiscip Genomics. 2024;6(1):1-5.

suscripcion

issnes

eISSN L 3072-9610 (English)

Information

Use of data and Privacy - Digital Adversiting

Infomedic International 2006-2025.