Genetics and Entropy: Turning our gaze toward the thermodynamics of biological systems

Authors

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.37980/im.journal.ggcl.en.20252757Keywords:

entropy, hermodynamics, dissipative structures, DNA, cancerAbstract

A particular physical magnitude governs our existence in an unsuspected way: entropy, formulated from the Second Law of Thermodynamics. This review seeks to move beyond its traditional conception as an abstract notion of physics and to present it as a fundamental key to understanding how we arise, organize, and ultimately fade away. Entropy is examined from a biological and genetic perspective, drawing on rigorous scientific literature, both contemporary and classical, for its conceptual foundation. We explore how biological systems do not challenge the laws of physics but rather exploit them to sustain life, maintaining internal order at the expense of exporting entropy to the environment. The contributions of Schrödinger, Prigogine, and Lehninger are revisited to describe organisms as self-replicating dissipative structures capable of persisting through the extraction of negative entropy from their surroundings. In addition, the work of contemporary physicists such as Carroll and Greene is used to examine the intricate relationship between evolution and entropy. The informational dimension of entropy is also addressed through DNA, understood not only as a molecule but as a biological language. Finally, cancer and aging are explored as divergent pathways of a shared entropic principle. From the perspective of genetics and biology, life can be understood as a precise choreography of energy and information, whose progressive dissipation threatens the very continuity of existence.

Introduction

Every day we are confronted with “irreversible” and spontaneous phenomena that, at first glance, might not seem to warrant more than everyday interest; however, if we were to pause and reflect on them with even a basic knowledge of physics, many questions would likely arise.

Thus, simple facts such as, for example, a burned sheet of paper cannot return to its initial state; likewise, as we age, we cannot rewind our internal clocks and recover our youth.

At this point, we might ask ourselves the reason behind these everyday events and reflect on the famous and often-cited “arrow of time” that indicates the clear direction in which events move consistently.

As currently understood, everything obeys the laws of physics. The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that systems naturally progress from order to disorder (what is known as entropy, a tendency present throughout the universe) and that, in every spontaneous process, the total entropy of the system and its surroundings increases. Living systems, although they maintain order locally, contribute to the global increase in entropy, as we will see later [1].

However, it is important to clarify that the term “entropy” currently has several connotations. If we have encountered it before, we may be more familiar with the definition of entropy taught in biology and chemistry courses during our academic training, in which entropy was defined as the tendency of the universe toward disorder, as previously mentioned.

This entropy, in its thermodynamic connotation, is considered to be everywhere (from black holes to evolution and aging) and always tends to increase. As the disorder of a system increases, the number of available states of the system increases, and energy becomes less concentrated [2]. At this point, we may ask: what happens to living organisms?

From fertilization onward, the human organism constitutes itself as an open system that, through coordinated biological processes, achieves a complex and functional multicellular organization, maintaining internal stability despite the continuous increase in entropy inherent to biological processes. The living world is characterized by complexity and, paradoxically, by increasing order [3, 4].

Is life itself an exception to the rule? A challenge to the natural order?

Indeed, we live in a universe in which, despite increasing entropy, it is filled with ordered structures such as stars, planets, and even ourselves. But why does this occur? Understanding this means understanding life itself from its origin, which is essential for acting upon it and attempting to preserve it.

For biological systems to function, they must remain far from equilibrium. This “equilibrium” refers to the homogeneity of all elements that form part of a system, without gradients or differences within it or with the external environment. This valuable observation led to the development of “non-equilibrium thermodynamics,” which establishes that when a spontaneous reaction occurs, it tends toward a state of thermodynamic equilibrium and, in the process, becomes increasingly random or disordered. It is this increasing disorder or entropy of the system that allows the spontaneous reaction to persist; however, once the system reaches maximum entropy or equilibrium, the spontaneous reaction ceases: there is no energy gradient and all processes stop, including biological ones, which for living systems is equivalent to the end of life [1, 3].

As we will explore in the following sections, many of the statements that attempt to explain these phenomena are still considered theories or scientific interpretations in search of an answer to one of the most unsettling and important questions ever asked: How did life arise?

Entropy: A Word with a Sea of Interpretations

The term entropy, as mentioned, may have multiple operational definitions. In this sense, entropy in its classical thermodynamic conceptualization (as a measurable physical quantity of system disorder) is a very useful guiding thread that we will continue to use throughout this review [7].

However, among the various definitions of entropy, one is particularly useful when attempting to understand biological systems. The theoretical physicist and mathematician Ludwig Boltzmann defined entropy as the measure of the number of possible microstates of a system that produce the same macrostate [1]. If the number of possible microstates for a given macrostate is high, entropy is said to be high (the system is highly disordered); conversely, if the number of possible microstates is low, entropy is said to be low (the system is highly ordered) [5]. This interpretation primarily involves a concept of possibilities. Therefore, the greater the number of microstates compatible with the same macrostate, the greater the entropy and the lower the degree of macroscopic order [1, 6].

It should be emphasized, as will be discussed in later sections, that entropy goes beyond its thermodynamic conceptualization as “disorder” or the distribution of possibilities; for example, informational entropy corresponds to the amount of information contained in or transmitted by an information source [7]. This does not contradict or overlap with entropy in its thermodynamic conceptualization or with Boltzmann’s definition but rather offers another “lens” through which to view the same phenomenon. In other words, entropy has different nuances or planes depending on the context in which it is viewed, with interpretations complementing one another—hence its complexity and, at the same time, its beauty.

Entropy and Evolution

Entropy and evolution, as physicist Brian Greene points out, form a strange yet extraordinary pair on the path toward understanding the origin of life. Recent theories suggest that life on Earth developed under evolutionary pressure operating at the molecular level; this is known as “molecular Darwinism,” a chemical struggle for survival in which a series of mutations and configurations ultimately led to the first collection of cells recognized as life [8, 9].

Thus, Darwinian selection is considered a crucial point in the transition from inert matter to living matter.

Living Matter Evades Degradation Toward Equilibrium

Physicist Erwin Schrödinger stated in his renowned 1944 work What Is Life? that what differentiates a living system from a non-living one is its ability to continue performing activities, moving, and exchanging matter with its environment for a much longer period than expected, remaining far from thermodynamic equilibrium [10, 11].

When this does not occur, the system fades into a mass of inert matter. Schrödinger called this the “thermodynamic equilibrium state” or “state of maximum entropy,” in which all parts of a system reach thermal equilibrium at a uniform temperature. Beyond this point, no further changes involving heat release or transformations capable of generating useful work would be possible [10]. All energy would be uniformly distributed, preventing any further physical processes or life.

It is by avoiding rapid decomposition into this inert state of “equilibrium” that a living organism appears to be unique. As fascinating as this observation is, the question arises: how does the living organism avoid such decomposition? The answer is by eating, drinking, breathing, and, in the case of plants, assimilating—in other words, by carrying out what is known as metabolism, or the exchange and transformation of matter and energy [3, 10].

Open Systems and Entropy Flow

An isolated system does not exchange matter or energy with its surroundings, whereas an open system exchanges both [12]. Living organisms are not isolated; they are considered open systems [13, 14], and therefore the Second Law of Thermodynamics applies both to living systems and to their surroundings. This is referred to as “the two entropic steps,” a concept introduced by physicist Brian Greene [15]:

-

In the first step, a localized decrease in entropy occurs when ordered structures form within the living system using energy (the living system absorbs energy from the environment to organize itself) [15].

-

In the second step, a greater increase in entropy occurs in other parts of the universe through the release of residual heat into the environment [15].

Every process, event, or occurrence implies an increase in entropy. Thus, a living organism continuously increases the entropy of the universe: it produces and exports “positive entropy” (heat) while maintaining order within itself [16].

Schrödinger introduced the concept of “negative entropy” (abbreviated as negentropy) as the basis of biological organization, proposing that living beings “feed” on order (solar light) to maintain their structure far from equilibrium [10, 14]. In this context, negentropy describes local processes of organization that occur within the general framework imposed by the Second Law of Thermodynamics [7].

In an organism, the degree of internal disorganization is entropy, and the degree of internal organization is negentropy. In other words, in a metaphorical sense, negentropy is systematically used as a synonym for a cohesive force, while entropy is a synonym for a repulsive force [7, 17].

Life, therefore, operates within the Laws of Thermodynamics. What is essential in metabolism is that the organism manages (or attempts) to rid itself of as much entropy as it inevitably produces while living, in order to avoid death [14].

Biological Illustrations of Entropy

The previous point was well summarized by the chemist Albert Lehninger as follows:

“The order that is produced within cells as they grow and divide is more than compensated for by the disorder they create in their environment. Life preserves its internal order by taking free energy from the environment and returning an equal or greater amount in the form of heat and entropy” [18].

To make these somewhat abstract concepts easier to understand, a few simple examples are presented below.

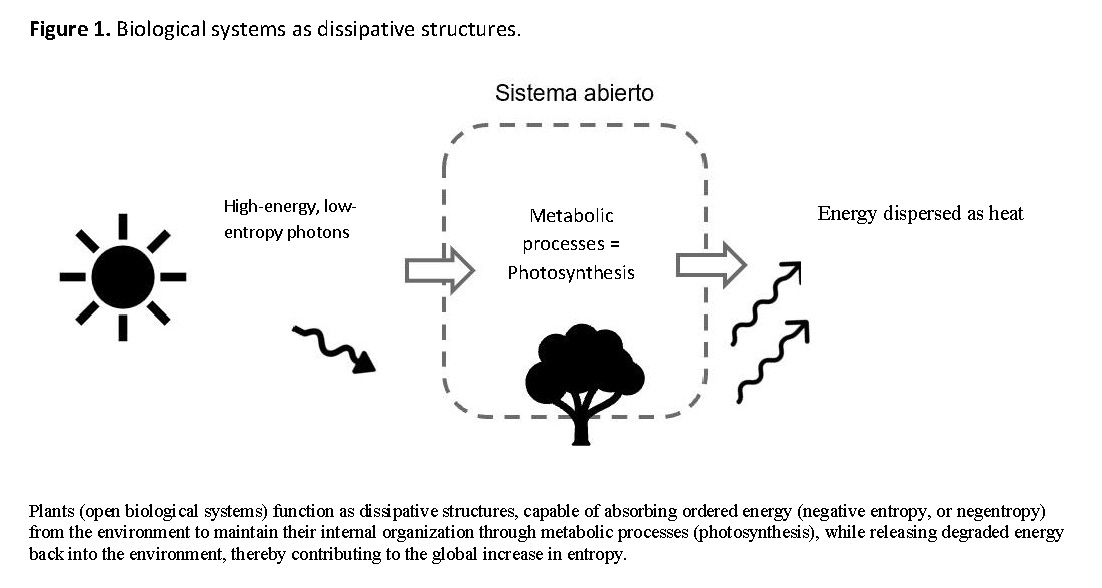

The ultimate source of all our energy and negative entropy is solar radiation. The Earth is therefore considered a system closed to the exchange of matter but open to the exchange of radiation with space. This exchange of radiation with space drives and sustains almost all processes occurring on Earth [3, 19].

Plants are also a clear example of this principle. Photons (energy with low entropy and therefore high order) are absorbed by plants, and cellular machinery uses them to maintain cellular functions. For every photon received from the Sun, the Earth sends back into space a much less ordered collection of energy-depleted and widely dispersed photons [15, 18].

Living Organisms as Dissipative Structures

For the physicist and chemist Ilya Prigogine, evolution needed to be reconceptualized as the study of the emergence, change, propagation, and adaptation of networks of “self-replicating dissipative structures” [20]. In thermodynamics, a dissipative structure is one that arises spontaneously in systems far from equilibrium, is maintained by consuming free energy, and efficiently increases entropy in its surroundings [12, 21].

The Second Law of Thermodynamics postulates that all actions increase disorder in the system in which they occur and consume usable energy in doing so [22]. From this perspective, life can be considered to have emerged as a consequence of physical processes that favored structures capable of dissipating energy.

Biological systems are self-organized dissipative structures. They absorb energy from their environment to maintain vital processes and then release heat back into the environment, operating in a non-equilibrium state [21].

To better understand life, therefore, a thermodynamic perspective is required—one that views living organisms as structures emerging from the dissipation of free energy in complex systems, evolving through natural selection to reproduce their structure and to use and degrade free energy more efficiently (Figure 1) [22].

Processes: Energy and Information

The processes and conditions that occurred in the past have shaped what living organisms have become today. Living organisms are systems that evolve because they have been “informed” by the environments in which they live. Their form and organization did not arise spontaneously but rather as the result of irreversible events (mutations and natural selection) that left permanent traces [9, 23].

These processes can be grouped into three well-defined points:

1) Energy Flow and Biological Mass

The first process is the maintenance and production of biological mass through the use of available energy and matter. Without a continuous flow of energy, phase separation from the environment would be lost, increasing the risk of reaching thermal equilibrium [23, 24].

-

Transformations that generate heat produce “thermal entropy”: a measure of the cost of maintaining biological structure [25].

-

Conservative transformations produce “structural entropy”: a measure of the system’s structural complexity [25].

2) Information Storage and Transmission

Second, biological systems maintain their structural and functional integrity through the storage and transmission of information. Without the accumulation and expression of information, biological systems could not retain successful patterns of energy flow that enhance their ability to maintain order [23].

Genetic information is a particular type of information. In deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), nucleotides form arrangements with both entropic and representational properties, generating hierarchical levels of integration: triplets → amino acids → proteins → regulatory functions, where each level imposes constraints on the lower ones [24, 26].

The informational entropy of a system depends on the number of possible configurations that the initial information can adopt. Thus, an informational macrostate (such as a functional gene) may be expressed through many possible microstates (sequence variants), and its entropy reflects these probabilities [24].

As Prigogine indicated, living beings are informed autocatalytic systems; therefore, the “internal production rules” that determine much of the biological forms upon which selection operates are determined by information transmitted to the system from ancestral systems [26].

3) Multilevel Entropy Production

Finally, as a consequence of energy flow, different types of entropy are produced at different rates [23]. There is not a single organizational level, but multiple levels, each interacting with the others in different ways:

-

At microscopic (cellular) levels, metabolism dominates: entropy is dissipated as metabolic heat, and organisms behave as classical dissipative structures [24].

-

At broader and longer-lasting scales (genetic and evolutionary processes), entropy is linked to genetic diversity [24].

Genetic information can thus be considered a form of organized entropy: a stable record of the energetic flow that gave rise to life, thereby linking thermodynamic principles with molecular evolution [27].

From Physics to Molecular Biology

Living matter, Schrödinger speculated, was governed by an “aperiodic crystal or solid.” In the mid-1940s, he expressed the following hypothesis: “We believe that a gene, or perhaps the entire chromosomal fiber, is an ‘aperiodic solid’” [10].

This type of non-repetitive molecular structure, which harbored “the encrypted code of heredity,” would give rise to “the complete pattern of the individual’s future development and functioning in maturity,” thus providing an early description of DNA [2].

Schrödinger therefore deduced—later reaffirmed by physicist Sean Carroll—that the stability of genetic information over time is best explained by the existence of this aperiodic crystal, which stores information in its chemical structure [28]. This insight inspired Francis Crick to abandon physics in favor of molecular biology, eventually leading to his discovery with James Watson of the DNA double helix structure [2].

In Watson’s own words:

“From the moment I read What Is Life? by Schrödinger, I concentrated all my efforts on finding the secrets of the gene” [2].

Organization at the Cellular Level

Living organisms are complex, ordered, and improbable entities. They possess extraordinarily low entropy because natural selection endowed them with adaptations that ultimately allowed genetic replication [6].

Each diploid cell contains two copies of each chromosome. These cells, distributed throughout the body, communicate with each other with great efficiency thanks to the genetic code. Their regular and orderly development is governed by this guiding principle in every cell, giving rise to events that are paradigms of order [3, 29].

According to Schrödinger, there are two distinct mechanisms through which order is achieved: one that produces order from disorder (metabolism) and another that produces order from order (replication) [2, 30].

Replication is a complex process and requires highly ordered and complex organisms. If an organism succeeds in surviving and reproducing, the genes encoding these adaptations are able to replicate. These genes can therefore be identified as the replicators in this process, with the organism acting as their medium of selection [6, 31].

The other mechanism—order arising from disorder (previously discussed)—is the one most commonly observed in nature and allows us to understand the broad trajectory of natural events, including their irreversibility.

DNA

If entropy exists throughout the universe, does it also exist in DNA? The answer is yes, but not in its thermodynamic sense of disorder; rather, as a measure of information (complexity, variability, or predictability). What does this imply?

Up to this point, entropy has been addressed as a physical quantity associated with energy and microstates. However, when the object of study is DNA, entropy acquires a different nuance: it does not describe energy flows but is instead used as a measure of information content and sequence complexity [32].

Most biological systems (including the human genome) contain information in the form of DNA. It is within these physical systems that store and process information that the Second Law of Thermodynamics operates to generate complexity, diversity, and biological order.

In these systems, large and structurally complex DNA sequences contain regions that have accumulated a high content of “erratic DNA” during evolution; in this context, DNA can be viewed as a structure far from equilibrium [32]. Although complex, biological information can be expressed in entropic terms: the more information a system contains, the greater the entropy it possesses within the informational framework [7, 32].

The lack of consensus regarding the biological meaning of entropy and genome complexity, as well as the different ways of evaluating these data, makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the causes of variation in genomic entropy among species [33].

Informational entropy, as a measure of information content and complexity, was first introduced by the mathematician Claude Shannon in 1948. Since then, it has adopted various forms and methodologies for analysis [32, 34, 35].

Shannon entropy quantifies the statistical unpredictability of elements (such as nucleotides) within a sequence: a message with high predictability has lower information content than a less predictable message [36, 37]. By contrast, topological entropy evaluates structural complexity and local variations, providing an approximate characterization of randomness. Thus, low topological entropy in a sequence implies that it is less chaotic and more structured [32].

Along these lines, Vopson proposed the principle of “mass–energy–information equivalence.” In simple terms, systems evolve toward states of lower informational entropy by reducing randomness, thereby increasing their capacity to store and control information [27].

In the human genome, it is estimated that approximately 5% of DNA is under selective pressure, but only about 1.5% of this DNA is considered coding. This implies that non-coding DNA elements are also under selective pressure and therefore perform significant functions [38].

Where Is Entropy Higher, Then?

The results are contradictory. Some studies have estimated that non-coding DNA has lower entropy than coding DNA, whereas three studies (Mazaheri et al., Koslicki, and Jin et al.), using topological entropy, concluded that non-coding DNA has higher entropy than coding DNA [38].

Recent studies applying definitions of topological entropy to systematic random samples of genes from all chromosomes of the human genome have concluded that introns have higher entropy than exons [32]. What might explain this result?

It is known that entropy measures the randomness of a DNA sequence, and introns are expected to behave in a more random manner because they are under lower selective pressure, contain fewer functional signals, and are therefore less conserved than exons [32].

The entropy of chromosome X, in both introns and exons, is significantly higher than that of chromosome Y [32].

In Koslicki’s study (Table 1), the mean entropy of introns on chromosome X was 3.5 standard deviations higher than the mean entropy of introns on chromosome Y. This study also showed that introns on chromosome Y exhibited an atypically low and bimodal entropy distribution, possibly corresponding to random sequences (introns with high entropy: greater than 0.910) and intronic sequences with hidden structure or function (low entropy: less than 0.910) [32].

What About Other Regions of the Human Genome?

Siepel et al. demonstrated that both 5′ and 3′ UTR regions are among the most conserved elements in vertebrate genomes. Therefore, the topological entropy—that is, the degree of sequence variation—of these regions is very low, indicating a high degree of structural organization [38].

DNA entropy is also influenced by nitrogenous bases.

In several studies, entropy profiles generated for 16 prokaryotic genomes revealed differences in complexity between genomes rich in cytosine–guanine (CG) and adenine–thymine (AT). In these studies, all CG percentage profiles showed the greatest increases when coding DNA was included, which is known to be richer in CG than non-coding DNA [4].

All of this supports the assertion that topological entropy can be used to detect functional regions and regions under selective constraint [24]. Thus, genetics—although it may not initially appear to be as closely associated with entropy as other sciences—plays a central role in its understanding.

The Human Being as a Biological System

In evolutionary biology, although still debated, there is an idea that small populations may accumulate duplications or repetitive elements that increase genome size while exhibiting “lower informational entropy” because the number of valid microstates for a functional macrostate is restricted. In other words, these would be large genomes with high redundancy [39].

In this sense, there appears to be an apparent lack of direct correspondence between increases in genome size, structural genome complexity, and measured entropy values. This discrepancy does not reflect a true contradiction but instead arises from the use of different definitions of entropy to describe the same phenomenon.

These conceptual distinctions help explain why a DNA region may exhibit high informational entropy (indicating highly variable or unpredictable sequences) without implying greater functional or organizational disorder. Likewise, functionally and evolutionarily conserved regions display low informational entropy—not due to structural simplicity, but because natural selection severely restricts the set of viable sequences. In this framework, entropy ceases to be an abstract notion of “disorder” and instead becomes a measure of the “diversity” of functional configurations accessible to the biological system [4, 24, 32].

Therefore, discussing entropy and its relationship with DNA requires a rigorous explanation of the definition being used—thermodynamic, Boltzmann, or informational. Once this framework is clearly defined, the apparent contradictions disappear, and the different measures become complementary tools for determining function, conservation, complexity, and patterns of organization within the genome.

In biological terms, the human being is an extraordinary machine composed of hundreds of systems, each designed to play a vital role in ensuring that this biological system functions and survives. Consequently, deviation from order in just a few atoms within the group of regulatory atoms in the germ cell is sufficient to produce a well-defined change in the organism’s hereditary characteristics on a large scale.

From the potential order we are capable of achieving, we are also susceptible to experiencing alterations in these processes, which can lead to structural disorganization, making us prone to adverse processes (malformations, disruptions, uncontrolled growth) and, depending on their severity, may lead to death [40].

When cellular order is lost, entropy increases. This often translates into accelerated and disorganized proliferation. A simple change in the usual order gives rise to increased entropy and adverse consequences.

Cancer cells are a clear example of this phenomenon.

Cancer and Entropy

A fundamental transition in the evolution of life was the shift from unicellular to multicellular organisms. At this stage, each cell had to transfer its primary qualities (survival and reproduction) to the organism as a whole [39].

Some of these cancer cells evolve toward an invasive and metastatic stage. Therefore, some authors classify cancer as a degradation of biological systems of information and communication [40].

What Is the Role of Entropy in Cancer?

The concept of entropy—whether structural, genomic, transcriptomic, or related to signal transduction—has been repeatedly applied to the characteristics of cancer tissues and cells. Among these, increased signaling entropy has been extensively studied as a hallmark of cancer [41].

Here, only three points are highlighted as particularly relevant for understanding this relationship.

First, the genesis of cancer and its relationship with entropy is extremely complex. Signaling entropy within a cell may favor the emergence of oncogenic events, for example, through the loss of negative control over cellular proliferation. Additional advantageous changes further increase competitiveness, allowing the tumor cell to accumulate sufficient advantages to become independent of normal physiological regulation [39].

Likewise, the diversity of mutation combinations found across different cancer types is the result of entropy-driven mechanisms, such as proto-oncogene activation or tumor suppressor gene inactivation, combined with cancer-specific mutations (passenger or facilitating mutations) [39].

In summary, the collective burden of perturbations in cancer cells destabilizes gene regulatory networks, increasing signaling entropy. This rise in entropy makes cancer cells more prone to transitions between cellular states and even between cell types [41].

However, the relationship with entropy does not end there.

Aneuploidy resulting from defective mitosis is a common cause of increased signaling entropy in cancer, leading to enhanced cellular proliferation [39].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are precise regulators of cellular biology and can therefore be considered ideal guardians against entropy increase. The role of negative regulation by miRNAs in cancer has been widely studied. Across different tumor types, a global decrease in miRNA levels has been documented, as well as defects in various stages of miRNA synthesis, primarily due to epigenetic silencing [39].

Resistance to Oncologic Treatment

It has also been shown that cancer therapy itself can impose an accelerated increase in entropy in cancer cells. This allows cancer cells to explore a broader region of the “gene expression phase space,” giving them the opportunity to reach normally latent “attractors” (states of minimal energy) corresponding to more aggressive phenotypes. Ultimately, this favors the emergence of new mutations and leads to resistance to therapies targeting existing oncogenic mutations [42].

This phenomenon has been observed, for example, in melanoma treatment and similarly in breast cancer, where preexisting quiescent cancer cells resistant to tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) have been identified [39, 42].

Aging and Death

Life, as portrayed throughout this work, does not reject entropy but rather experiences and lives with it until reaching an inevitable final collapse. Yet just before this collapse, another situation arises in which entropy plays a dominant role in its genesis.

Entropy and aging are closely related: aging can be interpreted as a consequence of increasing entropy. The integrity of gene regulatory networks declines with age, as observed in animal models, where analyses of dozens of tissue-specific gene expression datasets in aged mice and humans reveal overexpression of inflammation, apoptosis, and senescence pathways [39].

As extensively reviewed, entropy in systems always tends to increase. Shannon entropy has been shown to increase with age, as do CpG sites (regions of DNA where cytosine is followed by guanine) in Horvath epigenetic clocks (biological age markers), showing higher entropy—that is, greater variability in methylation patterns [31]. In this way, the relationship between entropy and aging is established.

But this is not the only relationship. From a thermodynamic perspective, the human being is a dissipative structure far from equilibrium; however, with aging, this system progressively loses efficiency in exchanging and distributing energy, including the transfer of negative entropy from the environment to the organism, making it more susceptible to disease and death [31].

Over time, the human being thus loses the ability to dissipate and counteract the increasing flow of positive entropy (the disorder accumulated over time), eventually approaching thermal equilibrium, where energy flow ceases and the system collapses.

Conclusions

Life can be understood as a natural process compatible with the Second Law of Thermodynamics, allowing biological systems to maintain a high degree of local order at the cost of increasing entropy production in their environment, thereby acting as open and dissipative systems.

This perspective proposes a reading of life as one of the many ways in which these laws can manifest in systems far from equilibrium. Thus, life maintains its internal structure not outside entropy but within its limits, using it as a means of dynamic stability.

As discussed throughout this work, entropy frames and conditions biological processes—from conception, development, and growth to aging. From a medical standpoint, it manifests as a silent axis underlying the biological mechanisms that clinicians observe, study, and address in each patient, in both physiological and pathological processes.

Entropy is involved in macroscopic and microscopic processes, including adverse events such as cancer, but it also maintains a remarkable relationship with the evolutionary processes that have shaped what we are today. It is impossible to speak of human survival without acknowledging that life has confronted and prevailed over (though not defeated) the immeasurable entropy that surrounds us day after day.

It remains to be determined whether this entropy-driven dual cadence can be sustained on cosmological scales or whether, in the long term, the universe will evolve toward a state of maximum entropy in which no energy gradients remain, leading to the so-called “heat death” of the universe.

I would like to conclude this brief reflection with the words of theoretical physicist and one of the leading proponents of string theory, Brian Greene:

“We all, in one way or another, try to make sense of the world around us. And all these elements lie at the core of modern physics. The story is among the grandest: the expansion of the entire universe; the mystery is among the most difficult: discovering how the cosmos arose… and the quest is among the deepest: the search for fundamental laws that explain everything we see and everything beyond, from the tiniest particles to the most distant galaxies” [43].

Acknowledgments

Thanks are extended to Dr. Enrique Daniel Austin-Ward, MD, Geneticist, Centro Nacional Especializado de Genética Médica y Genómica, Caja de Seguro Social, Panama, for his contributions.

References

[1] Pierce, S.E. (2002). Non-equilibrium thermodynamics: An alternate evolutionary hypothesis. Crossing Boundaries. 1. 49-59

[2] Gherab-Martín, K. (2023). Erwin Schrödinger: física, biología y la explicación del mecanismo de la vida. TECHNO Review, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.37467/revtechno.v13.5143

[3] Ho, M. W. (1994). What is (Schrödinger’s) negentropy? Modern Trends in BioThermoKinetics, 3(1994), 50-61.

[4] Simões, R. P., Wolf, I. R., Correa, B. A., & Valente, G. T. (2021). Uncovering patterns of the evolution of genomic sequence entropy and complexity. Molecular genetics and genomics: MGG, 296(2), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00438-020-01729-y

[5] Greene, B. (2011). The hidden reality: Parallel universes and the deep laws of the cosmos. Vintage Books. ISBN: 978-0307278128

[6] Devine S. D. (2016). Understanding how replication processes can maintain systems away from equilibrium using Algorithmic Information Theory. Bio Systems, 140, 8–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystems.2015.11.008

[7] Isa, H., & Dumas, C. (2020). Entropy and Negentropy Principles in the I-Theory. Journal of High Energy Physics, Gravitation and Cosmology, 6, 259–273. https://doi.org/10.4236/jhepgc.2020.62020

[8] Kolchinsky A. (2025). Thermodynamics of Darwinian selection in molecular replicators. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 380(1936), 20240436. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2024.0436

[9] Adamski, P., Eleveld, M., Sood, A., & others. (2020). From self-replication to replicator systems en route to de novo life. Nature Reviews Chemistry, 4, 386–403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-0196-x

[10] Schrödinger, E. (1944). What is life? The physical aspect of the living cell. Cambridge University Press. Online ISSN: 1538-7445

[11] Trapp, O. (2021). First steps towards molecular evolution. In A. Neubeck & S. McMahon (Eds.), Prebiotic chemistry and the origin of life. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81039-9_7

[12] Barbacci, A., Magnenet, V., & Lahaye, M. (2015). Thermodynamical journey in plant biology. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6, 481. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00481

[13] Baez, J. C., & Pollard, B. S. (2016). Relative Entropy in Biological Systems. Entropy, 18(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/e18020046

[14] Yazdani, S. (2019) Informational Entropy as a Source of Life’s Origin. Journal of Modern Physics, 10, 1498-1504. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2019.1013099

[15] Greene, B. (2020). Until the end of time: Mind, matter, and our search for meaning in an evolving universe. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN: 978-0525432173

[16] Sánchez, F., & Battaner, E. (2022). An Astrophysical Perspective of Life. The Growth of Complexity. Revista mexicana de astronomía y astrofísica, 58(2), 375-385. https://doi.org/10.22201/ia.01851101p.2022.58.02.16

[17] Cohen, I. R., & Marron, A. (2020). The evolution of universal adaptations of life is driven by universal properties of matter: energy, entropy, and interaction. F1000Research, 9, 626. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.24447.3

[18] Lehninger, A. L., Nelson, D. L., & Cox, M. M. (2000). Lehninger principles of biochemistry (3rd ed.). Worth Publishers. ISBN: 9783662082904

[19] Wu, W., & Liu, Y. (2010). Radiation entropy flux and entropy production of the Earth system. Reviews of Geophysics, 48, RG2003. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008RG000275

[20] Prigogine, I. (1977). Self-organization in nonequilibrium systems: From dissipative structures to order through fluctuations (G. Nicolis & I. Prigogine, Eds.). Wiley. ISBN: 978-0471024019

[21] Crecraft H. (2023). Dissipation + Utilization = Self-Organization. Entropy (Basel, Switzerland), 25(2), 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/e25020229

[22] Cushman S. A. (2023). Editorial: The role of entropy and information in evolution. Frontiers in genetics, 14, 1269792. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1269792

[23] Brooks, D. R., Collier, J., Maurer, B. A., Smith, J. D. H., & Wiley, E. O. (1989). Entropy and information in evolving biological systems. Biology & Philosophy, 4(4), 407–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00162588

[24] Schmitt, A. O., & Herzel, H. (1997). Estimating the entropy of DNA sequences. Journal of theoretical biology, 188(3), 369–377. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.1997.0493

[25] Sherwin, W. B. (2018). Entropy, or Information, Unifies Ecology and Evolution and Beyond. Entropy, 20(10), 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/e20100727

[26] Prigogine, I. (1977). Time, structure and fluctuations [Nobel Lecture]. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB.

[27] Mendoza Montano, C. (2025). Toward a thermodynamic theory of evolution: A theoretical perspective on information entropy reduction and the emergence of complexity. Frontiers in Complex Systems, 3, 1630050. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcpxs.2025.1630050

[28] Carroll, S. M. (2010). From Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time. Dutton. ISBN: 978-0452296541

[29] Seely A. J. E. (2020). Optimizing Our Patients' Entropy Production as Therapy? Hypotheses Originating from the Physics of Physiology. Entropy (Basel, Switzerland), 22(10), 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/e22101095

[30] Price, M. E. (2017). Entropy and selection: Life as an adaptation for universe replication. Complexity, 2017, Article 4745379. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4745379

[31] Zhang, B., & Gladyshev, V. N. (2020). How can aging be reversed? Exploring rejuvenation from a damage-based perspective. Advanced genetics (Hoboken, N.J.), 1(1), e10025. https://doi.org/10.1002/ggn2.10025

[32] Koslicki, D. (2011). Topological entropy of DNA sequences. Bioinformatics, 27(8), 1061–1067. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr077

[33] Mazaheri, P., Shirazi, A. H., Saeedi, N., Reza Jafari, G., & Sahimi, M. (2010). Differentiating the protein coding and noncoding RNA segments of DNA using shannon entropy. International Journal of Modern Physics C, 21(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0129183110014975

[34] Natal, J., Ávila, I., Tsukahara, V. B., Pinheiro, M., & Maciel, C. D. (2021). Entropy: From thermodynamics to information processing. Entropy, 23(10), 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/e23101340

[35] Takens, F. (2010). Reconstruction theory and nonlinear time series analysis. In H. W. Broer, F. Takens, & B. Hasselblatt (Eds.), Handbook of dynamical systems (Vol. 3, pp. 345–377). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1874-575X(10)00315-2

[36] Thanos, D., Li, W., & Provata, A. (2018). Entropic fluctuations in DNA sequences. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 493, 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2017.11.119

[37] Huo, Z., Martinez-Garcia, M., Zhang, Y., Yan, R., & Shu, L. (2020). Entropy Measures in Machine Fault Diagnosis: Insights and Applications. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 69(6), 2607-2620. Article 9037369. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2020.2981220

[38] Thomas, D., Finan, C., Newport, M. J., & Jones, S. (2015). DNA entropy reveals a significant difference in complexity between housekeeping and tissue specific gene promoters. Computational biology and chemistry, 58, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2015.05.001

[39] Tarabichi, M., Antoniou, A., Saiselet, M., Pita, J. M., Andry, G., Dumont, J. E., Detours, V., & Maenhaut, C. (2013). Systems biology of cancer: entropy, disorder, and selection-driven evolution to independence, invasion and "swarm intelligence". Cancer metastasis reviews, 32(3-4), 403–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-013-9431-y

[40] Gryder, B. E., Nelson, C. W., & Shepard, S. S. (2013). Biosemiotic Entropy of the Genome: Mutations and Epigenetic Imbalances Resulting in Cancer. Entropy, 15(1), 234-261. https://doi.org/10.3390/e15010234

[41] Nijman S. M. B. (2020). Perturbation-Driven Entropy as a Source of Cancer Cell Heterogeneity. Trends in cancer, 6(6), 454–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2020.02.016

[42] Francescangeli, F., De Angelis, M. L., Rossi, R., Cuccu, A., Giuliani, A., De Maria, R., & Zeuner, A. (2023). Dormancy, stemness, and therapy resistance: Interconnected players in cancer evolution. Cancer Metastasis Reviews, 42(1), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-023-10092-4

[43] Greene, B. (2010). The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions, and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN: 978-0393338102

suscripcion

issnes

eISSN L 3072-9610 (English)

Information

Use of data and Privacy - Digital Adversiting

Infomedic International 2006-2025.